If we knew what we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?

Albert Einstein

Jargon-filled abstruse titles of scientific publications are easy to mock. Take this title from a 1986 report in the Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology: “Specific Enzymatic Amplification of DNA In Vitro: the Polymerase Chain Reaction.” While many people would know a definition of most of the individual words in the title, few would have grasped the scientific meaning of the title. Nor could they have envisioned the revolution it would spawn in the study of genetics, evolution, human health and, most recently, biodiversity measurements.

President Trump has been deploying an old bipartisan tradition to vilify research by derisively citing such titles. From 1975 to 1988, Democratic Sen. William Proxmire of Wisconsin gave a monthly Golden Fleece Award to federally sponsored studies that he deemed had fleeced the American taxpayer with expenditures on unworthy topics. No doubt some research is a waste of taxpayer funding, but quick and casual assessments are unlikely to distinguish the wheat from the chaff.

Let’s take the example of polymerase chain reaction – what even many nonspecialists now know as PCR – a method that allows scientists to make quick, unlimited copies of DNA fragments to have enough DNA to detect and study.

The research on polymerase chain reaction won the 1993 Nobel Prize in chemistry for Kary Mullis and Michael Smith. However, the PCR reaction would have been impossible without the temperature stable polymerase enzyme that had been isolated from bacteria discovered during basic research by microbiologist Thomas Brock.

While visiting Yellowstone National Park in 1964, Brock was struck that there seemed to be bacteria thriving in springs that were sometimes near boiling. In a 1969 paper with a title that is indecipherable by any but the bacterial taxonomist, Brock named one of the bacteria: “Thermus aquaticus gen. n. and sp. n., a Nonsporulating Extreme Thermophile” in the Journal of Bacteriology. An enzyme from this species became Taq polymerase, an abbreviation of the hot springs bacterium’s genus and species names, on which Mullis’ later idea about PCR depended.

Mullis’ insights and ideas for experiments that led to PCR famously came to him in imaginative scientific reverie on long drives along the California coast. Mullis had knowledge from Brock’s basic federally funded basic research, an incredible imagination about how to apply Brock’s knowledge, and private capital to figure out how to generate enough copies of DNA to study.

The whole package of work wasn’t carefully coordinated and was pursued by different scientists with diverse motivations. Nevertheless, the collection of research turned out to be a transformative public-private partnership. In the subsequent two decades, PCR revolutionized medicine and society by enabling rapid disease diagnosis, making genetic testing widely accessible, and transforming forensic science through DNA fingerprinting. The technology accelerated genomic research including the Human Genome Project, enhanced global public health surveillance, and democratized molecular biology with more affordable, portable tools. From COVID-19 testing to personalized medicine, PCR’s impact on health care, research, and criminal justice has been profound. In 2022, the annual global market for PCR instruments and supplies was $37 billion.

Part of that PCR-fueled growth industry is bringing a different kind of potentially huge scientific and societal benefit.

It started with a 2008 scientific paper with a title that is reasonably easy for the lay person to understand: “Species Detection Using Environmental DNA From Water Samples.” Environmental DNA or eDNA refers to genetic material in cells sloughed from an organism’s skin or excreted into the water, soil or air. Gentile Ficetola and co-authors reported in Biology Letters that the amount of American bullfrog eDNA detected in water samples from French ponds corresponded to the abundance of bullfrogs known to exist from traditional biological surveys. That study immediately started an agenda of applied research in my laboratory and hundreds of other university and government laboratories around the world.

It turns out that all organisms – not just humans at crime scenes or American bullfrogs in French ponds – leave a measurable trail of DNA behind. And if the copies of eDNA are multiplied with PCR, they become readily detectable. Hundreds of studies have improved eDNA methods, and compared eDNA results to conventional surveillance and monitoring efforts for many plants and animals in different aquatic and terrestrial environments. For most use cases of environmental monitoring, eDNA is at least complementary to existing methods. For some use cases, eDNA is more accurate, cheaper, and faster.

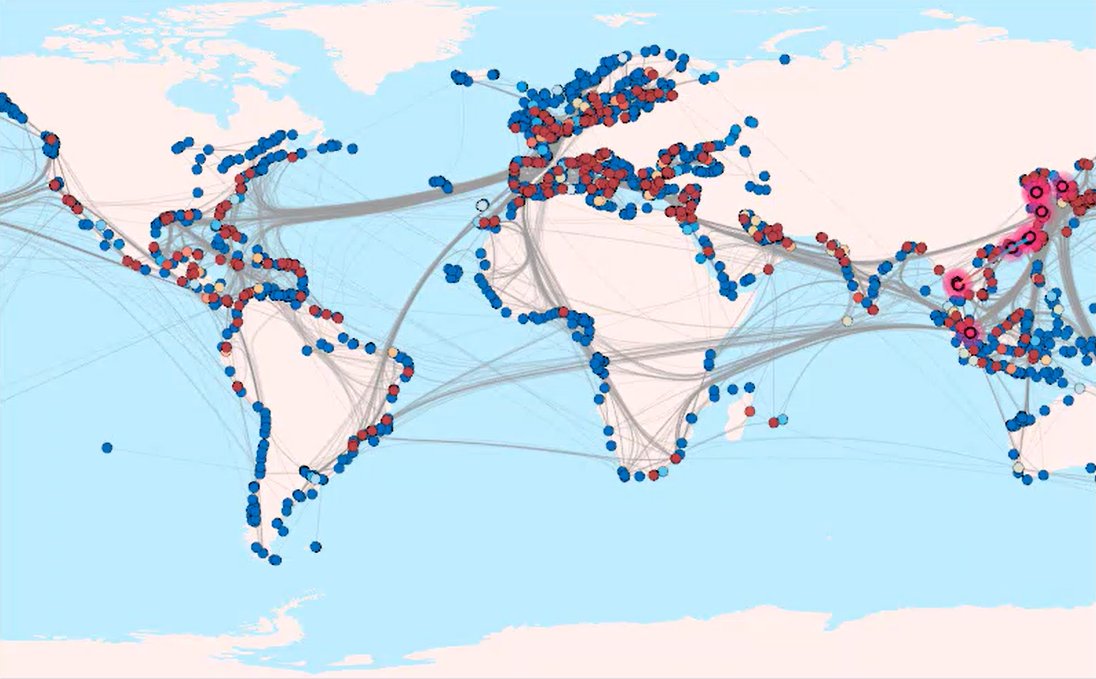

How else could you census all existing species and simultaneously provide an index of their abundance in large aquatic environments, and repeat those measurements to detect change over time? For example, my co-authors and I used a jargony title in a 2023 issue of Molecular Ecology to communicate our discovery that “Environment and Shipping Drive Environmental DNA Beta-Diversity Among Commercial Ports.”

In other words, funding from the National Science Foundation allowed us to collect eDNA from water samples from ports around the world, and show that environmental conditions like temperature and salinity determine the distributions of species (no surprise there), and that the patterns of species spread beyond their natural ranges reveal the network of global shipping. Using eDNA, it is now possible to more comprehensively and quickly provide sensitive and accurate surveillance for alien species threatening the biosecurity of many nations, whether ships, planes or enemy military are the spreaders of the harmful species.

"Ports tightly coupled by frequent shipping in a cluster are likely to introduce non-native species to each other."

From: Jian Xu, Thanuka L. Wickramarathne, and Nitesh V. Chawla,

Representing higher-order dependencies in networks,

Science Advances 2, no. 5 (2016): e1600028.

(View narrated video visualization.)

From Thomas Brock to Kary Mullis to Gentile Ficetola to my lab, the throughlines of research are not straight and narrow. Rather in the story I’ve told, one curiosity-driven, federally funded discovery led to a diverse set of additional basic and applied results with huge, tangible impacts on human health, environmental health, biosecurity, and economic development.

The research project whose title you find indecipherable and laughable today may make environmental protection more efficient and effective or save the life of you or your grandchild tomorrow.

Header photo: Mushroom Pool, in the Lower Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park, as it looked in June 23, 1967.

The sample that would be the source of Thermus aquaticus strain YT-1 came from this hot spring.

Pictured is Thomas Brock standing near the edge of the pool.

Image from the self-published “A Scientist in Yellowstone National Park” (Brock, 2017).

Learn more about David M. Lodge