When we were kids, loudly asking “who cut the cheese?” was a part of crass juvenile humor when the car or classroom suddenly got smelly. While the origins of this expression may be lost on people who have never cut into a rind of Limburger, the relationship between cheese and gas, especially methane, has gained recognition and is more important than ever.

Dairy-derived gases – mostly from burps and manure – accounts for about 2% of annual U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. To combat this, dairy production must be well managed to coexist with things we all want, such as forests, clean water and a stable climate. A priority of Cornell Atkinson is to minimize the undesirable side effects of dairy production while producing nutritious food and fostering traditional cultures in the US and globally. The key to accomplishing this is deep research collaboration across the university and long-term partnerships between the university and other sectors.

Last month’s post highlighted some of the reasons that corporations, NGOs, and government agencies can find universities difficult to work with. In this post, we want to share some success in overcoming those impediments to reduce the methane gas footprint of dairy production.

First, a little history. Cornell’s recent work is a continuation of astonishing progress in U.S. dairy production over the last 50 years, including these advances in the Northeast:

- The average milk production per cow has increased 150%. This has occurred in concert with a 49% reduction in the total number of cows, with a net result of a 27% increase in total milk production in the region.

- The greenhouse gas intensity of milk production – the amount of greenhouse gas produced per gallon of milk produced – has decreased 42%, and absolute emissions lessened by 24%.

- Improved health care for cows and pasteurization of milk have reduced the occurrence of dairy foodborne illness to practically zero.

- Cow waste management has improved such that runoff of nitrogen and phosphorus has decreased 47%, resulting in higher water quality.

These dramatic improvements in production efficiency and waste management stem from advancements in animal breeding and genetics; improvements in production of corn silage, grass and other components of cow feed; and in providing finely tuned diets. They have been fueled largely by USDA and other government sponsored research at universities, especially land grant universities like UC-Davis, UW-Madison, and Cornell.

But we have a lot of work to do. Methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide; even small amounts have a large effect on atmospheric warming. Therefore, efforts to further decrease methane emissions from cows are crucial to stabilize the climate.

One of the newest efforts lies in developing feed additives that reduce methane emissions. These have proved promising in short-term studies, but their long-term efficacy and their impact on milk productivity and cow health are only now being tested. At Cornell we worked with Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) to design a rigorous protocol for testing the effectiveness of such additives. In 2024 it was adopted by the Food and Drug Administration, and is now practiced at Cornell and elsewhere.

For decades, dairy researchers have been refining cow diets to optimize milk production while maintaining cow health in different climates and at different stages in the cow’s life. The Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System guides the diet recipes for about 70% of U.S. dairy cows. Discoveries from ongoing research on cow nutrition and feed additives are constantly used to refine the system, quickly scaling improved practices across the country. As a result, the efficiency of milk production continues to rise, and methane emissions per gallon of milk produced continue to fall.

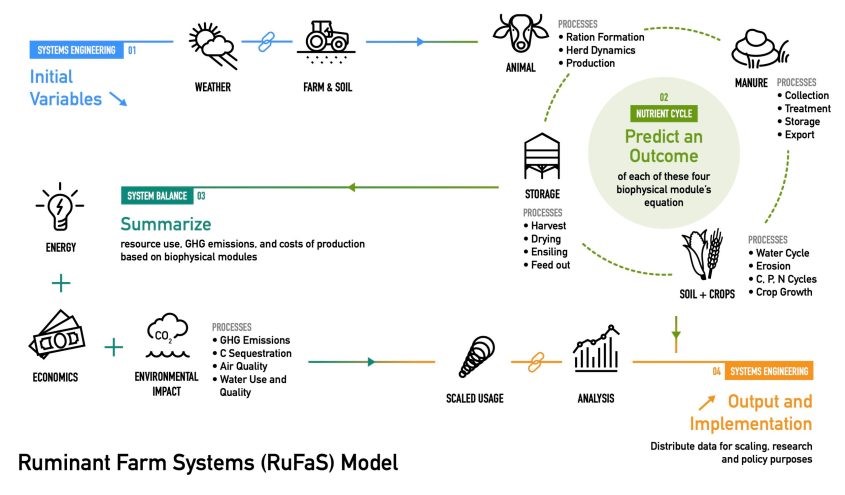

At Cornell Atkinson, we’ve also provided support to continuously improve a whole dairy farm system model called the Ruminant Farm Systems (RuFaS), which was developed at Cornell with with many academic partners and USDA support. It is now promoted by the nation’s largest dairy co-op through FARM and the corporate association Dairy Management Inc. for use across the U.S. RuFaS considers all farm inputs and outputs, including how and where the ingredients for cow food are produced and how waste is managed.

We are partnering with New York State Energy Research and Development Authority to install an experimental anaerobic digester next to one of Cornell’s dairy barns for experiments to capture and use methane from manure and human food waste as a fuel instead of releasing it into the atmosphere. Research results will inform the design and operation of full-scale digesters increasingly being installed at commercial dairies.

These examples illustrate that the key to successfully reducing dairy farm methane emissions is developing strong partnerships across sectors. As Britt Groosman, EDF’s senior vice president for agriculture, water and food, told us, “The Cornell-EDF partnership has been the essential bridge between academic innovation and real-world implementation, connecting corporate partners and government stakeholders to drive meaningful change”.

In recent years, Cornell Atkinson has provided expert faculty and staff leadership, cross-college coordination, and program management, in addition to over $1.25 million, to seed these research-to-impact activities. Cornell University’s Colleges of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Veterinary Medicine, and Engineering, along with PRO DAIRY and other Cornell Cooperative Extension efforts, have contributed incalculable intellectual capital and research infrastructure linked to stakeholder networks. EDF, TNC, and the Clean Air Task Force have contributed their expertise in moving information into policy. The Global Methane Hub, the Gerstner Family Foundation, and other philanthropists have provided in excess of $13 million in additional funding. Finally, corporations, including Danone, Cargill and Mars, and the association Dairy Management Inc. have provided additional funding, leadership, and expertise.

Most important, all these parties helped co-create the multiple strands of work to reduce the methane footprint of dairy products. Thanks to these collaborative efforts, we can look forward to cutting our cheese with less climate impact.

Learn more about David M. Lodge, Daryl Nydam, and Patrick Beary