There are two vocal extremes about policy engagement in universities. Some have no interest in how policy is affected by or affects university research topics and opportunities. Others have become advocates, and even activists, for specific energy-related university or government policies. I’d like to think the middle ground is growing, including the honest broker approach championed by Roger Pielke Jr.

At Cornell Atkinson, we focus on being an honest broker of information and research to inform public opinion, corporate practices and products, and government policies on climate, energy, food and health. We are non-partisan, engaging university expertise with NGOs, corporations and government agencies, when and where it is relevant to problems ripe for solution. Government policy, the outcome of partisan politics, often determines the ripeness of problems.

Therefore, it is important to understand what the electorate is saying about what they want. Wearing their advocacy hats, academics are often more keen to tell the electorate what it should want, rather than to listen to what it does want, as suggested by David Brooks’ recent column, “Voters to Elites: Do You See Me Now?” No one likes to be the object of condescension.

This brings me to the (Republican) elephant in the room in the wake of the U.S. presidential election.

There are loud and clear messages from the electorate that elite academic institutions often ignore at the peril of further erosion of trust in universities. Trump’s 10-point plan for universities puts us in the crosshairs, and we need to listen.

By electing a candidate who has said climate change is a hoax, voters are not saying they don’t care about climate change or protecting the environment. According to AP VoteCast, more voters in 2024 (7%) than in 2020 identified climate as their top concern. Plus, a large number of people who voted for Trump, also voted for local ballot initiatives to increase their taxes to pay for land conservation and improved climate resilience.

This is not a contradiction. People care about more than one thing, and often, the things they care about compete. This election year, 59% of voters identified the economy or immigration as their top concern and reducing pocket-book costs as most important. Voters may feel that nationwide climate policy mandates have contributed to inflation, and that such policies were imposed by elites from perches in ivy covered ivory towers. When competing aspirations are represented by competing candidates, voters choose the nominee that talks most about their highest priority need, which for a majority of U.S. voters was Donald Trump.

Political pundits and historians will be parsing 2024 voter data for years, but class division was clearly an important factor in voter choice. More than 65% of the electorate was without a college degree, and 55%–56% of those voted for Trump, increasing to 63% for those who never attended college at all. About 55% of voters making less than $100,000 annually, representing 63% of U.S. households, voted for Trump.

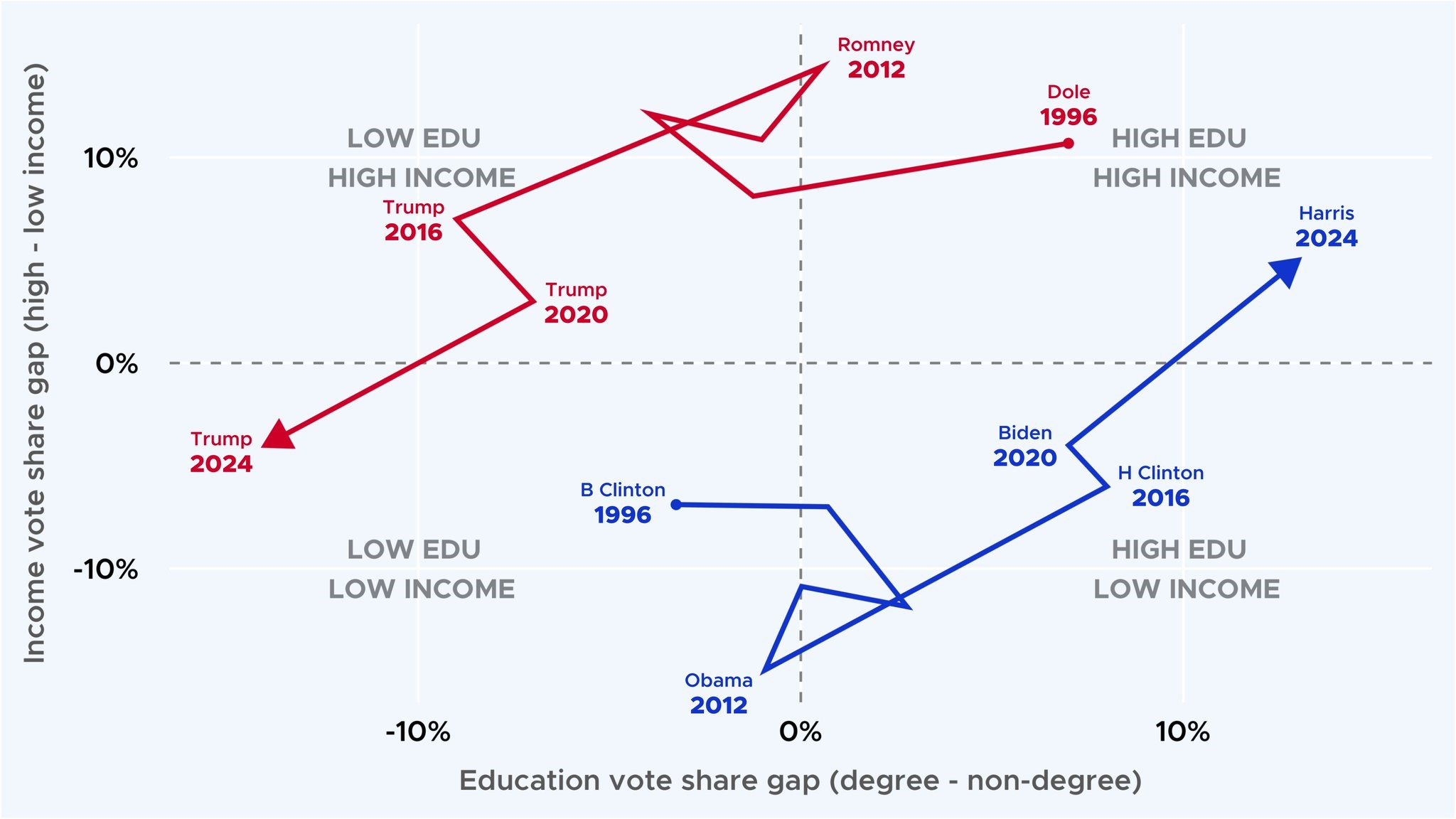

For both education and income, these percentages were greater than they were in 2016 and 2020, which is the continuation of a trend, not a fluke. As Patrick Flynn of Focaldata recently illustrated on X (reproduced here with permission), the proportion of U.S. voters in the lower half of the income distribution and without a college degree who voted Republican, has been increasing for many election cycles. In contrast, the Democratic Party has gradually become the party of wealthy, college-educated elites.

Patrick Ruffini saw this coming in his 2023 book, “Party of the People: Inside the Multiracial Populist Coalition Remaking the GOP,” suggesting there is a voter realignment underway, and a key fault line is class.

Trump voters are far more likely than Harris voters to need to choose weekly among rent, food and health care, especially in the inflationary economy of the last three years. The weekly family budget takes priority over what may seem to be the paramount concerns of their college-educated peers: subsidizing college debt by all taxpayers; naming and dividing us by identity group; and executing climate policies that may stoke inflation.

No matter how true it is that everyone–rich and poor, college educated and high school educated–will benefit eventually from more aggressive policies to enhance climate mitigation and adaptation, there will be no such policies without voter support.

The 2024 election suggests that voter support depends on effectively addressing the short-term concerns of less privileged voters. Policies that decrease the wealth gap will not only be more just; they will also be more politically feasible.

Clearly, there is more work to be done in universities and government to design, assess and communicate policies that more fairly distribute the costs and benefits of climate and energy policies.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act has incentivized private sector investment that is projected to produce at least 160,000 manufacturing jobs in batteries, solar panels, carbon capture and other climate-responsive industries in the U.S. over the next four years. Cornell’s Climate Jobs Institute has helped design policies that advance the energy transition and create well-paying jobs. While this is a start, I do not know now what a comprehensive agenda to meet this imperative looks like.

I am certain that this research must take center stage. If elite universities do not better serve the whole of society, we will remain in the crosshairs.

Learn more about David M. Lodge